Water is roughly 800 times as dense as air, which affects

nearly every aspect of its behavior, starting with the typical speeds it moves

with. High winds, such as in hurricanes, can move 32 m/s (74 mph), while a

rapid ocean current, such as the tides of Cook Inlet, Alaska, move at 5 m/s (11

mph). Despite that, the much denser water has far greater momentum. A cubic

meter of air at hurricane velocity has the same momentum as a cubic meter of

water moving 4 cm/s!

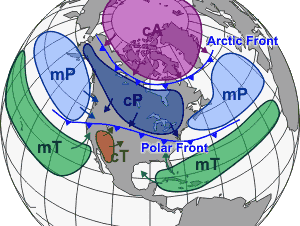

A parcel of air or water tends to move with a collective

momentum. Being a fluid, the mass can change shape if impacted by topography or

a neighboring air or water mass, but it does not collapse. Two air or water

masses which encounter each other will not merge and blend properties. They

will by and large maintain their separate qualities, with some turbulence and

mixing along the boundary, or front, between then.

In the atmosphere, the front between a warm and cold mass of

air is frequently marked by thunderstorms, or precipitation of some sort. In

the ocean, such a front is the site of some mixing and formation of eddies, or

swirls. Another common process in the ocean is "entrainment", when a

moving parcel of water--for example, the warm Gulf Stream moving north through

the cold Atlantic--drags, or entrains, a large amount of neighboring water along

with it, through friction.

That entrained water over the course of many hundreds of miles does mix with and become part of the original water of the current. The current becomes cooler, the entrained water warms up, and the overall volume of the former Gulf Stream becomes the North Atlantic Current, bringing five times as much water as it started with.

The Gulf Stream and North Atlantic Current, via thermal satellite imagery.

An air or water mass generally dissipates, except for

stable, long-term formations such as the Polar High, a dome of cold, high

pressure air over the Arctic, or Antarctic Bottom Water, a layer of very cold,

very dense water which spreads northward through the Atlantic from its

Antarctic source. After a low-pressure, warm storm system has spent its heat

energy, the low pressure rises and the air temperature is equalized with its

surroundings. Simiarly, the North Atlantic Current ends its life as cold water

which is as cold or colder than the water around it (another topic we will

revisit later). Friction and mixing processes along the front will gradually

erode and eliminate it.

Weather and current systems are dominated by the dynamics of

these very large bodies of air and water which move in more or less unitary

fashion. We have already seen a bit of this in the post on thunderstorms, and

will continue to observe it in future posts on ocean currents and atmospheric

features such as the Polar Vortex.

Tomorrow: wind circulation

Be well!

No comments:

Post a Comment