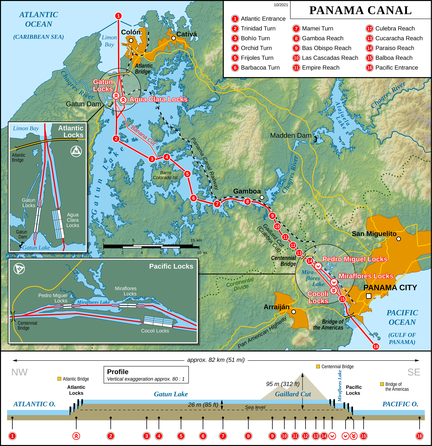

The Panama Canal, which connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans via the Isthmus of Panama, is the conduit to an estimated 3% of world trade (by comparison, 12% runs through the Suez), cutting the trip around South America by weeks. It is 82 km/51 mi long and was begun in 1888 by France, but when investor confidence faltered after many worker deaths, the United States too over in 1904, completing the project in 1914. In 1999 the nation of Panama took full control of the canal’s operation, though, in competition with China, the United States maintains the power by treaty to defend it against any influence which would seek to close it off to any innocent (i.e. commercial) traffic.

The Isthmus of Panama.

Among the many challenges were the mountainous terrain, requiring ships to be lifted as much as 25 m/85 ft above sea level through a series of gravity-fed locks, and dropping them down again on the other side of the isthmus (where the Atlantic and Pacific ocean levels differ mostly due to tides, which are larger on the Pacific side). The locks are basically dams, through which water is allowed to flow under control and so gently raise or lower the ships in transit. Building this lock system created the gigantic Lake Gatún, which is the central part of the canal passage.

Lake Gatún is the source of water for the lower locks, and normally has no trouble meeting the canal’s transit needs. However, in 2019, a strong El Niňo brought a drought of more than five months which lowered lake levels to the point that the Panamanian authority restricted travel through the canal until Gatún was sufficiently replenished. That has led to debates within Panama about creating more artificial lakes, to serve as water reserves. Environmentalists are firmly against this plan, saying that the trade of forest for artificial lake is inherently bad. The likelihood of increasingly strong El Niňo events in the coming century threatens to put the use of the canal at risk.

Cross section of the canal.

Compared to transit around Cape Horn on South America’s tip it is claimed that the Panama Canal reduced carbon emissions by more than 13 million tons in 2020. While economizing is good, the larger issue is the general growth of the economy which these efficiencies empower. Another example is America’s interstate highways, which after their creation in the 50’s and 60’s were objects of amazement, allowing fast, easy travel across the country. Specifically, California’s highways in the early 60’s brought about a new way of life. But within a decade, the number of cars and drivers on those same highways had risen to a level where horrendous traffic jams and dangerous levels of pollution were commonplace.

Lake Gatún.

So with the Panama Canal: the current canal, with modern efficiencies, carries more than four times the ship tonnage it was originally designed for, and has become an integral part of a world economy which has grown sixteen times larger ($81T vs. $5T global GDP) since the canal first opened (3% of $81T is $2.4T, nearly half the 1914 world economy). Of course the Panama Canal is not responsible for the world’s entire economic growth. But it is intertwined, and simply citing modern efficiencies is far from understanding its role in facilitating greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. One crude measure is by global CO2 emissions, which were 31.5 GT in 2020: 3% of this, 945 MT, represents trade which passed through the Panama Canal that year. This is not to condemn the use of the canal: it is to emphasize, however, that efficiencies are worthwhile only when applied wisely, not used as an attempted shortcut around nature.

Gaillard Cut, Lake Gatún.

Be brave, and be well.

No comments:

Post a Comment