The average annual temperature in Poland has increased by 2.0°C/3.6°F since 1950, about twice the world rate. This is consistent with much of Europe sharing the intensified warming of the Arctic. Despite persistent fears of the shutdown of the North Atlantic current (the entire Gulf Stream would not shut down: it would simply head east from North Carolina to Spain, instead of continuing north to Greenland), temperature records show tremendous disproportional warming in continental Europe along with the Arctic, and models do as well. Knowing the mathematical basics of geophysical fluid dynamics, but not being a professional modeler myself, I can tell you that this aspect of the modeling—predicting further warming for Europe despite fears of the North Atlantic circulation weakening or ending—is a point of the models worth some attention.

Temperature is expected to continue rising across the whole of the country, especially in winter and spring. Precipitation in the mountainous region of southern Poland is predicted to continue the trend toward increasingly severe events punctuated by drought, with a moderate increase in overall amount.

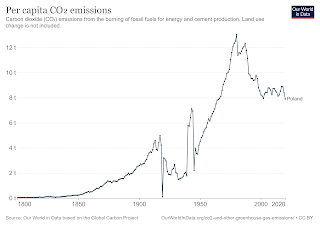

Poland accounts for 10.5% of the European Union’s carbon emissions, though it is nearly twice as carbon intensive (measured in tons CO2 emitted per $ GDP), though this represents progress since 2005, with a fall of 44%, though its raw emissions have remained roughly consistent. In this respect Poland is performing better than most industrialized nations, whose emissions, aside from the economic effects of COVID-19, have increased. However, as is all too often the case, progress to reduce and eliminate emissions is yet to happen.

Tomorrow: introduction to the Middle East.

Be brave, and be well.