The spatial scale and speed of changes occurring in the ocean and coastal environments exceed anything in the past several thousand years. As in terrestrial ecosystems, overall warming, poleward species migration. Seasonality in the ocean, as marked by events like plankton blooms, is changing, with warm phases occurring earlier and lasting longer. As temperatures rise, oxygen levels and ocean pH are falling.

From the IPCC's 6th Assessment Report, Volume 2, Chapter 3. Marine birds (top) and marine mammals (bottom) impacted historically (blue) and predicted (red) by various environmental factors.

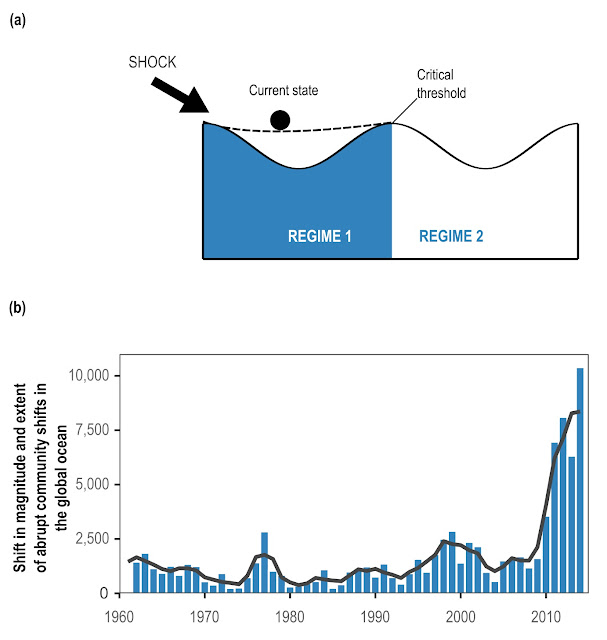

From the IPCC's 6th Assessment Report, Volume 2, Chapter 3. (Top) the tipping point. Repeated shocks make it easier for a given system to move from one previously stable state to another stable state, with different baseline conditions. (Bottom) Change index, a measure of factors like temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen and other chemical indicators and population counts, over time.

Marine heat waves—periods of abnormally high water temperatures in a given region—are occurring more frequently, and with higher temperatures. Large heat-related die-offs have happened in ecosystems as diverse as coral reefs, rocky shores, kelp forests, seagrasses, mangroves, and even the Arctic Ocean. The ocean’s rising heat content also worsens unrelated problems like eutrophication. The presence of fertilizers and man-generated organic waste leading to plankton blooms which deplete the water’s oxygen content, particularly along the coast, and warmer water increases the speed with which this occurs. Pollution and erosion from human developments near the coast put stress on coastal communities like mangroves, which are then less able to resist climate stressors like heat and acidity.

From the IPCC's 6th Assessment Report, Volume 2, Chapter 3. Climate velocity at various depths (by row) and various climate scenarios (by column). Climate velocity = how far poleward would animals need to migrate to remain in the same conditions they live in now.

From the IPCC's 6th Assessment Report, Volume 2, Chapter 3. Century difference (2000-2100) models for overall biomass of various classes of organisms.

The poleward migration of species is stressing all species living in the more-crowded conditions, as more species compete for food and breeding areas, even while the equatorial zones are comparatively hollowed out of life. This affects not only the natural ecosystems but also human fisheries, where increasingly diverse populations mean reduced catch of the target fish and shellfish, and more bycatch. Meanwhile increased human output of chemicals into the water is leading to higher levels of toxins in the marine animals, plants and algae, stressing them all and toxifying our food supply.

From the IPCC's 6th Assessment Report, Volume 2, Chapter 3. Modeled impacts of climate change, with and without human mitigation, on coral reefs.

From the IPCC's 6th Assessment Report, Volume 2, Chapter 3. Coastal erosion (red) and accretion (blue) modeled at various time scales and climate scenarios.

Sea level rise is damaging coastal communities, especially tidal pool environments, as the shoreline migrates inland and upward. Salt water intrusion is also making coastal freshwater saline, which impacts human and natural communities alike. One of the world’s most glaring examples of this is the Florida Everglades, formerly a twenty-mile-wide freshwater river flowing from Lake Okeechobee to the Atlantic. Sea level rise and massive water withdrawal by humans have resulted in lower lake levels and higher ocean levels, causing the water’s flow to reverse, with salt water migrating northward, gravely damaging the prior communities and changing the entire ecosystem from freshwater to marine.

From the IPCC's 6th Assessment Report, Volume 2, Chapter 3. Threats which impact various regions of the oceanic environment.

Tomorrow: Water.

Be brave, be steadfast, and be well.

No comments:

Post a Comment